Introduction

Mainstream 3D video games are largely inaccessible to blind and low vision (BLV) players because they lack crucial accessibility tools. One way to provide greater accessibility is by providing players with a sense of spatial awareness of their surroundings. BLV players must heavily rely on spatial awareness tools (SATs) to gain this awareness; whereas, sighted players can rely on sight as well. In order to make video games more accessible to BLV players, a major accessiblity challenge is to understand how existing approaches to facilitating spatial awareness assist BLV players and what these tools' relative merits and limitations are.

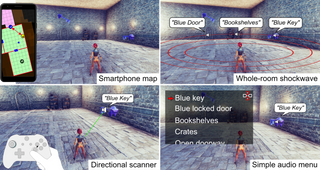

To address this challenge, we investigated four leading approaches to facilitating spatial awareness that represent a broad range of design choices — a smartphone map, a whole-room shockwave, a directional scanner, and a simple audio menu of points-of-interest — and uncovered new insights into this class of game accessibility tools.

Current Approaches to Spatial Awareness

"Spatial awareness," as used in our work, refers to a user's awareness of their surrounding environment and how they are situated within that environment. We performed our investigation with respect to six distinct aspects of spatial awareness that we identified through existing research in cognitive map formation and spatial awareness for people with vision impairments within the physical world. These aspects of spatial awareness include knowledge of:

- The scale of an area.

- The shape of an area.

- The user's own position & orientation within an area.

- The presence of items within the area.

- The arrangement of items within the area.

- Areas adjacent to the player's current area.

Games made for BLV audiences often use ambient signals to provide implicit spatial awareness to players — usually taking the form of environmental audio cues that communicate information about the surrounding environment.

A scene from The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (Nintendo, 2017). The main character, Link, is standing next to a waterfall. If a player hears a waterfall around them, then they are aware of the presence and relative position (if 3D sound is used) of that waterfall — thus contributing to their spatial awareness.

These ambient signals, however, can become less useful to players as environments become more complex (as is the case with many mainstream games). As such, accessible game designers often turn to creating tools that explicitly communicate spatial awareness to players. These tools — or spatial awareness tools (SATs) — supplement implicit spatial awareness cues by clarifying environmental information and affording players greater control over what information they hear and when they hear it.

User Study

With our user study, we wanted to understand what aspects of spatial awareness BLV players find important and how well today's SAT approaches facilitate the various aspects of spatial awareness. Game designers and developers can benefit from having a clearer idea as to which SAT(s) they should pick to integrate within their games, especially since they often have limited resources and thus cannot implement everything.

We investigated four approaches to giving BLV players spatial awareness of their surroundings:

- a smartphone map — a smartphone-based, touchscreen map that represents the use of tactile maps & displays to grant spatial awareness,

- a whole-room shockwave — an acoustic room-based shockwave utility inspired by echolocation techniques,

- a directional scanner — taken from our previous work with NavStick which repurposes a game controller's right thumbstick to allow a user to "look" in any direction they wish, and

- a simple audio menu — that lists out the contents of the area that the player is currently in and is used in many "audiogames" created for visually impaired players.

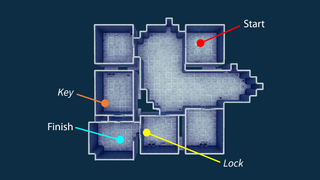

To investigate these approaches, we created a 3D third-person adventure game called Dungeon Escape, which consists of four levels set within an indoor dungeon environment. Players must reach a goal checkpoint in each level by finding objects (such as keys) that allow them to clear obstacles (such as locks). We performed this study with nine visually impaired participants, who were given one of the four tools to use in each level. We obtained participants' sentiments via a series of questionnaires.

An overhead view of a game level within Dungeon Escape, the 3D video game we created for our user study. Participants had to pass through multiple rooms, collecting keys and opening locks to eventually reach the finish.

Study Results

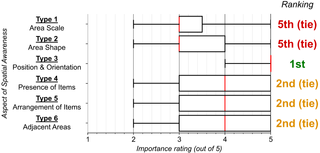

In terms of the relative importance of the six types of spatial awareness to BLV players: Participants thought that knowledge of their position & orientation (spatial awareness type #1 above) was the most important in that it was always helpful in knowing their current situation within the area as part of planning future actions. Below that was a three-way tie between item presence, item arrangement, and adjacent areas awareness (types #4, #5, and #6) which participants thought could help, but could also be too much information at times. Finally, tied at the very bottom were area scale and shape awareness (types #1 and #2) which participants thought were unnecessary much of the time.

The importance of the six aspects of spatial awareness within games for BLV players. Responses were given by participants on a five-point unipolar Likert scale. Higher values indicate that that aspect of spatial awareness was more important to participants. Red lines indicate median ratings within this box plot. Rankings based on median ratings are shown to the right.

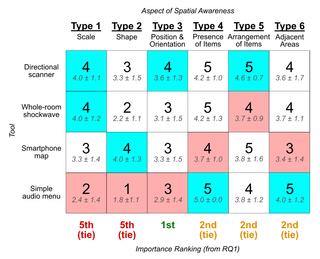

In terms of how well the four SATs facilitated the six types of spatial awareness: Despite position & orientation being the most important types of spatial awareness, participants felt that none of the four tools excelled at communicating position & orientation. Participants generally felt that they were unable to clearly ascertain where they were within the room and the world at large using any of the tools. Furthermore, participants greatly desired the ability to combine tools and customize their experience using the SATs. (See the full paper for all of our results.)

Participant ratings for how well each SAT approach facilitates each type of spatial awareness. Large text indicates median values, and small text indicates mean plus/minus standard deviation. Responses were given on a five-point unipolar Likert scale. Higher values indicate that, according to participants, that tool facilitated that aspect of spatial awareness well. Blue and red cells indicate the best and worst performing SAT approaches for each spatial awareness type (column), respectively. The importance rankings from our RQ1 analysis are shown again at the bottom.

Takeaways & Future Work

Our findings reveal several implications: BLV players will benefit greatly from further work in creating an effective tool for communicating position & orientation, and SATs should embrace customizability as a core feature. Furthermore, our investigations with tool combinations yielded that the combination of the directional scanner and the simple audio menu together gives players the greatest spatial awareness — that is, these two tools together provide better spatial awareness than any one tool by itself.

Beyond video games, we also see similar studies within the physical world to evaluate navigation tools built for blind and low vision users within physical world environments.

With our findings, we hope that accessible game designers will have a better understanding as to how SATs can provide a fulfilling yet accessible experience for BLV players within their games and thus open them up to an audience who may otherwise have been unable to play those very games.