Introduction

The vast majority of mainstream 3D video games are inaccessible to blind and low vision (BLV) players, and games created specifically for BLV audiences often lack the fun and engagement found in their mainstream counterparts. Prior work in game design has highlighted the importance of cultivating distinctive qualities within games to enhance their fun and enjoyment. One such quality is the sense of discovery.

When exploring game worlds, sighted players experience a world rich with choices driven by visual cues: perhaps they see something that piques their interest in the distance and run toward it or find an opening that might lead to new things. The joy players feel when they discover something new is central to their experiences within these worlds. However, games created for BLV players tend to reduce game worlds to simple menus that list out the contents of the world — robbing players of that element of discovery.

Some mainstream games, such as The Last of Us, attempt to bridge this gap by employing spatial audio cues to signify the locations of objects. However, such approaches generally guide players along predetermined paths, offering little in terms of exploratory freedom and the joy of discovery that is crucial to a fun gaming experience.

Screenshot from The Last of Us Part 2 (2020) showing the "enhanced listen mode," the game's spatial cues for BLV players. The white circles near the center of the image indicate locations of pings — one of the few sources of information BLV players have about their immediate environment.

An important challenge is to create a different way of approaching exploration so that BLV players can experience a genuine sense of discovery akin to that enjoyed by their sighted counterparts. In this project, we explore this challenge by designing, building, and testing Surveyor, an in-game assistive tool for facilitating a greater sense of discovery in BLV players.

Formative Interviews

To understand what scaffolding might be needed to support discovery, we conducted formative interviews with two veteran blind gamers. This formative study identified three major abilities essential for fostering a sense of discovery in BLV players:

- The ability to actively look around environments rather than solely rely on menus and maps to discover items.

- The capacity to maintain an exploration log, assisting players in tracking areas already explored and guiding future exploration to uncover new areas of the game world.

- The option to fast travel to previously discovered locations, allowing for more fluid gameplay.

Surveyor

Using the findings from our formative interviews, we created Surveyor, an exploration assistance tool for virtual worlds designed to facilitate a greater sense of discovery in BLV players. Our demo video shows Surveyor in action. Surveyor directly facilitates the three abilities we found in our formative interviews:

Looking around → Directional scanner

The ability to look around is fulfilled by the directional scanner, which we adapted from our previous work with NavStick and also investigated in our work with spatial awareness tools. Players simply tilt the right thumbstick on their game controller to scan their surroundings via their line-of-sight. Using 3D/spatialized audio, the tool announces objects-of-interest by name, while it indicates walls through a continuous white noise effect.

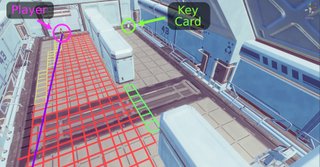

View of the player inside a room within our 3D video game testbed. They are using the directional scanner (represented by the purple line) to survey the area within their line-of-sight. Red cells represent areas within the player's current line-of-sight that have so far been swept via the directional scanner.

Exploration log → Surveyor's tracking system

Surveyor's exploration tracking system implements the exploration log. As players use the directional scanner to survey their surroundings, the system marks scanned areas as explored. This segments the room into a patchwork of explored and unexplored zones, which we refer to as "patches." Surveyor uses an underlying matrix-like data structure to keep track of these patches.

The borders (also called "edges") between explored and unexplored patches represent new opportunities for exploration. Surveyor's job is, thus, to highlight these edges so that players can — if they wish — move to them and use the directional scanner to investigate the unexplored patches.

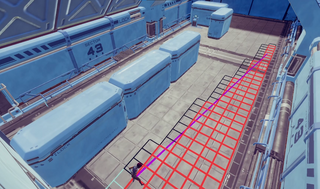

Depiction of Surveyor's exploration tracking system within our 3D video game testbed. Red cells represent areas within the player's current line-of-sight that were swept via the directional scanner. Areas behind the large crates remain unexplored.

Fast travel → Specialized menu system

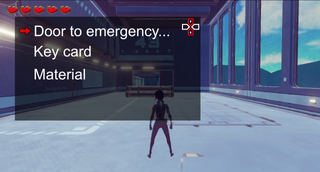

The fast travel ability is fulfilled by Surveyor's specialized menu system. This menu system contains four sub-menus, all of which allow players to place audio beacons at the points represented by the menu options:

- Edges of unexplored patches — allows users to quickly determine the number and location of unexplored patches within the current room.

- Landmarks already seen — allows users to quickly revisit any points-of-interest they have already encountered.

- Unexplored rooms within the greater world — highlights rooms that the user has not yet fully explored but have been encountered by the player (whether through the directional scanner or by physically exploring it).

- Fully explored rooms within the greater world — highlights rooms that the user has fully explored.

View of the four sub-menus of Surveyor's menu system within our 3D video game testbed.

User Study

Through our user study, we wanted to investigate how well Surveyor facilitates discovery and how players' experiences with Surveyor differ from those facilitated by existing in-game tools. We created a 3D adventure video game within the Unity game engine and implemented Surveyor within it. We also integrated two other tools representing the status quo:

- a simple audio menu of points-of-interest within the current room, representing existing techniques that simplify the world down to a list, and

- a shockwave utility that pings objects within the current room upon the press of a button, representing spatialization techniques found within The Last of Us games.

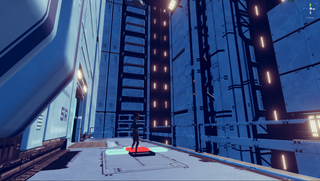

View inside a level within our 3D video game testbed.

Notable Results

Here, we report some notable findings from our study — this was a fully remote study we performed with nine BLV participants. Our academic publication (to be published at CHI 2024) contains more detailed study results.

Regarding Surveyor itself, participants felt that they were able to experience a strong sense of agency with the tool. Surveyor encouraged participants to explore the levels more, and this was evident in both the paths participants took as well as their verbal sentiments. Yet, some found Surveyor somewhat cumbersome to use. In particular, Surveyor elevated parts of the world that did not particularly matter to the task at hand — for at least two participants, they felt this to be cumbersome while some others stated that they would need some more time to get used to how Surveyor worked.

Regarding the simple menu, participants generally felt that it was easier to use than Surveyor and that Surveyor had a higher learning curve. However, many felt that this simplicity made the game much less interesting. One participant stated the following after their experience with the menu — as part of our counterbalancing scheme, they used the menu after using Surveyor:

Obviously, I'm not timing myself, but I felt like I went through it faster [than with Surveyor]. But fast doesn't always mean better. The whole thing just felt very, very sterile and very soulless. It was just, 'Here's what you have access to, and if you want to go there, press a button,' and sure, you have to move, but that's it.

View of the simple audio menu within our 3D video game testbed.

Finally, regarding the shockwave, every participant felt they were able to complete the levels quickly, and indeed, our own results showed that the shockwave facilitated the fastest level completion times of all three tools. However, participants did not feel they understood or felt immersed within the environment at all when using the shockwave. Furthermore, five participants expressed their disapproval of the tool within The Last of Us games — they noted that the games forced them to follow a predetermined path, and the audio feedback provided little information about objects outside of it. A couple of participants even admitted they did not finish either of The Last of Us games because of this.

View of the shockwave within our 3D video game testbed. The red circle on the floor represents the shockwave's current position.

Further Applications

Our work with Surveyor dealt with 3D/top-down game contexts. However, our explorations also yielded other domains where Surveyor-like systems could apply. For example, some 2D platformers, like Super Mario Bros., also contain an element of discovery — encouraging players to explore game levels to find items within areas that are hidden or initially inaccessible. A Surveyor-like system could potentially open up these games to BLV audiences and make their experiences within them more fun.

Screenshot from Super Mario Bros. Wii (2009), a 2D platformer game. The area below and to the left of Mario is currently blocked off but contains items to collect and explore.

Finally, prior work has noted a need for exploration assistance systems for BLV users within the physical world, allowing BLV users to explore and understand environments better. Though not accessibility-focused, platforms like Zenly — which was later acquired by Snap — have kept track of where people have and have not been, thus encouraging users to explore cities and other areas. Surveyor-like systems could also play a role in facilitating exploration within the physical world for BLV users.